Roxana Oana Darabont

1 University of Medicine and Pharmacy “Carol Davila” – Cardiology Department of University Emergency Hospital Bucharest

Contact address:

Roxana Oana Darabont, MD, PhD, Cardiology Department of University Emergency Hospital Bucharest, Splaiul Independentei Street, no. 169, 050098 Bucharest, Romania; fax: +40 21 3180576; phone: + 40 723 441 315. e-mail: rdarabont@yahoo.com.

Paragangliomas are rare tumors that grow from cells of the peripheral nervous system, which derive from the embryonic neural crest cel1,2. The head and neck represent the most common topography of these tumors. At this level they originate mainly from carotid body (carotid bifurcation), with other possible locations on vagal body, in the middle ear, and larynx. The carotid body paragangliomas (CBPs) are highly vascularized lesions, therefore one formerly name used for them was “glomus tumors”. Another ancient denomination – “chemodectoma” – was indicating their possible chemoreceptor function3.

CBPs are usually benign, non-secreting, slow growing tumors4,5. About 60% of them did not exhibit growth in follow-up. Some reports are indicating that 4.2 years is the average double time for this tumors6. CBPs can be found at any age, but the usual age for onset is between the third and six decade of life (mean age 55 years)7,8 and is slightly more frequent in women8. As a whole, carotid body tumors are bilateral in 10% of cases9.

The true incidence of CBPs is still unknown as long as many cases remain undiagnosed and the disease is very rare, but it is estimated to 0.012%10.

Keywords: carotid body paraganglioma, ultrasound, color Doppler ultrasound

We are presenting the case of 30 years old male with asymptomatic bilateral swelling of the neck which is the usual presentation in 60-70% of CBP11. During the clinical exam we found a palpable mass on each side of the neck, in front of the sternocleidomastoidian muscle, being more easier moved horizontally rather than vertically (the Fontaine’s sign)12.

In other cases a pulsating mass can be detected at palpation. Very rarely a carotid bruit can be heard, due to an important compression induced by the tumor on the carotid arteries. Large CBP may be associated with dysfunction of the vagal nerve or cranial nerves IX, XI, and XII, with Horner’s syndrome or deficits of the facial nerve13.

The usual diagnostic methods for this pathology are: B-mode and Doppler ultrasound, angio-CT, angio-MRI, 111 In-OctreoScan and digital subtraction angiography. Depending on carotid arteries involvement CBPs can be of three categories, according to Shamblin classification: class I – splaying of the carotid bifurcation with little attachment to the carotid vessels, class II – partial surrounding of the internal and external carotid arteries, Class III – complete surrounding of the carotid vessels14.

A relatively recent evaluation proved a sensitivity of 92% and a specificity of 100% for the B-mode combined with color Doppler ultrasound in the detection of carotid paragangliomas compared with CT/MRI. However, the difference in maximum diameter of the lesions measured at ultrasound versus CT/MRI was significant (p=0.008), ranging between – 5 mm and + 16 mm (mean difference 2.2±6.0)15.

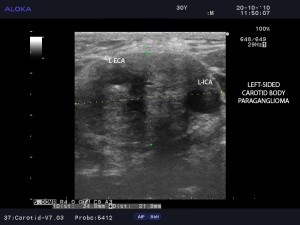

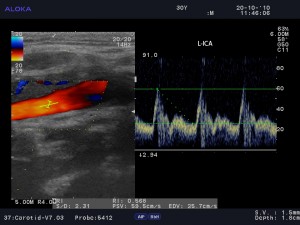

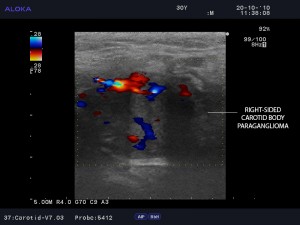

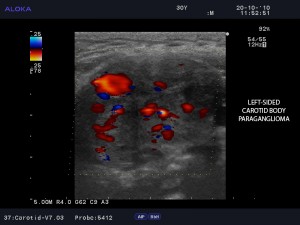

In our case the diagnostic of carotid body tumor was firstly established at ultrasound exam. An oval, well-defined, inomogenous, hypoechoic and hypervascularized structure was observed at carotid bifurcation on the right side of the neck (Figure 1 and 2) and on the left side as well (Figure 3 and 4). Figure 4 is indicating a CBP of Shamblin class III, with complete surrounding of the carotid arteries. In Figure 5 it is illustrated the attachement of CBP on the entire proximal wall of the left internal carotid artery in longitudinal view. Figure 6 is emphasizing that the flow is still normal in left internal carotid artery despite the adjacent invasion of the tumor.

Figure 1. B-mode ultrasound imaging of the right-sided carotid paraganglioma. The tumor is oval, well-defined, inhomogeneous, hypoechoic. Cranio-caudal diameter has 21.5 mm and tranversal diameter has 28.3 mm.

Figure 3. B-mode ultrasound imaging of the left-sided carotid paraganglioma with Shamblin class III characteristics – splaying of the carotid bifurcation and complete surroundings of the carotid arteries. Cranio-caudal diameter has 21.9 mm and transversal diameter has 34.8 mm. L-ECA = left external carotid artery; L-ICA = left internal carotid artery.

Figure 5. B-mode ultrasound imaging of the left sided paraganglioma attached to the proximal wall of the left internal carotid artery in longitudinal view. L-ICA=left internal carotid artery.

Figure 6. Color and spectral Doppler ultrasound of the left internal carotid artery indicating normal flow at this level; L-ICA = left internal carotid artery.

After three years of follow-up the patient did not proceed to surgical correction of the bilateral CBP taking into account that the tumors are asymptomatic, with very slow grow and the risk of intervention is significantly high.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

1. Najibi S, Terramani TT, Brinkman W et al. Carotid body tumors., J. Am. Coll. Surg., 2002; 194: 538-539.

2. Paal E, Chung EM, Head and neck pathology – Radiology classics: vagal paraganglioma, Head and Neck Pathol., 2007; 1: 35-37.

3. Martin TP. What we call them: the nomenclature of head and neck paragangliomas, Clin. Otolaryngol., 2006; 31: 185-186.

4. Myssiorek D, Ferlito A, Silver CE et al. Screening for familial paragangliomas. Oral Oncol., 2008; 44: 532-537.

5. Şanh A, Őz K, Ayduran E et al. Carotid body tumors and our surgical approaches, Indian J. Otolaryngol. Haed Neck Surg. 2012; 64:158-161.

6. Jansen JC, van den Berg R, Kuiper A. et al. Estimation of growth rate in patients with head and neck paragangliomas influences the treatment proposal, Cancer, 2000; 88: 2811-2816.

7. Sajid MS, Hamilton G, Baker DM. A multicenter review of carotid body tumour management. Joint vascular research group. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg., 2007; 34: 127-130.

8. Luo T, Zhang C, Ning YC et al. Surgical treatment of carotid body tumor: case report and literature review, Journal of Geriatric Cardiology, 2013; 10: 116-118.

9. Pacheco-Ojeda L. Malignant carotid body tumors: report of three cases. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol., 2001; 110: 36-40.

10. Grotemeyer D, Loghmanieh SM, Pourhassan S et al. Dignity of carotid body tumors. Review of the literature and clinical experiences. Chirurg, 2009; 80: 854-863.

11. Patetsios B, Gable DR, Garrett WV et al. Management of carotid body paragangliomas and review of a 30-year experience, Ann. Vasc. Surg., 2002; 16: 331-338.

12. Boedeker CC, Ridder GJ, Schipper J. Paragangliomas of the head and neck: diagnosis and treatment, Fam. Cancer, 2005; 4: 55-59

13. Offergeld C, Brase C, Yaremchuk S. et al. Head and neck paragangliomas: clinical and molecular genetic classification, Clinics, 2012; 67(S1): 19-28.

14. Shamblin WR, ReMine WH, Sheps SG et al. Carotid body tumor (chemodectoma). Clinico-pathologic analysis of ninety cases, Am. J. Surg., 1971; 122: 732-739.

15. Demattè S, Di Sarra D, Schiavi F et al. Role of ultrasound and color Doppler imaging in the detection of carotid paragangliomas, J. Ultrasound, 2012; 15: 158-163.

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a