Alexandra Buture1, Marin Postu1, Radu Ciudin1,2, Bogdan A. Popescu1,2, Carmen Ginghina1,2

1 „Carol Davila”University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania

2 Department of Cardiology, Emergency University Hospital, Bucharest,

Abstract: Syncope is defi ned as an episode of transient loss of consciousness caused by global cerebral hypoperfusion; its characteristics include a rapid onset, short duration, and spontaneous complete recovery1. The aetiology of syncope is complex and often elusive, with important prognostic implications2. Keywords: syncope, Holter monitoring, cerebrovascular disease.

CASE PRESENTATION

We present the case of a 61 year-old male patient who presented with repetitive episodes of syncope at rest, dizziness spells and lightheadedness over the course of the previous year. He associated multiple cardiovascular risk factors (active smoking, arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia) and had a known history of multi-vessel coronary artery disease spanning over two decades: he had undergone surgery for coronary artery by-pass grafting (CABG) in 1998 (left internal mammary artery/left anterior descending artery and internal saphenous vein/right coronary artery), had suffered an inferior myocardial infarction in 1999 and had had percutaneous angioplasty of the left anteri-or descending artery in 1999 with signifi cant reste-nosis revealed in 2007, when he underwent a repeat CABG procedure (free saphenous grafts to the left anterior descending artery, first diagonal artery, pos-terior interventricular artery). The patient associated peripheral artery disease (stage IIb Fontaine). Extra-cranial cerebrovascular disease had also recently been documented: a Doppler ultrasound examination had revealed diffuse carotid artery atherosclerosis with a right internal carotid artery stenosis evaluated at 60%.

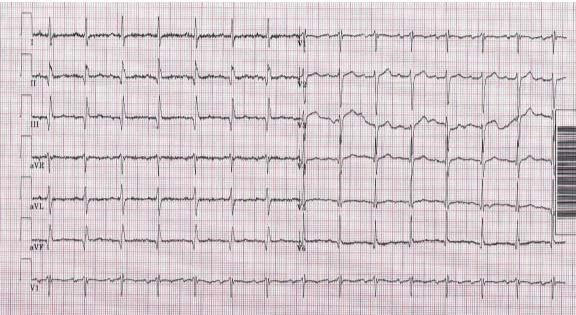

The clinical examination and blood panel were unremarkable. The resting ECG showed sinus rhythm with a frequency of 89 bpm, inferior necrosis sequelae and flat T waves in the lateral leads (Figure 1).

The transthoracic echocardiography showed a non-dilated left ventricle with moderate systolic dysfunc-tion (LVEF 40-45%), akinesia of the anterior septum, apex and infero-basal wall, mild mitral regurgitation, normal right chambers and pulmonary pressures.

To better evaluate the severity of the carotid artery stenosis and its possible role concerning the patient’s episodes of transient loss of consciousness, a carotid arteriography was performed, which revealed a non-critical 50-60% right internal carotid artery stenosis, without indication for revascularization (Figure 2).

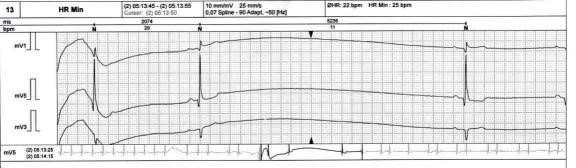

Other causes of syncope were then investigated. A 24-hour Holter monitoring was therefore performed, under beta-blocker therapy (he was receiving a 200 mg daily dose of metoprolol succinate as part of the treatment for his coronary artery disease), and sur-prisingly revealed multiple sinus pauses, the longest of which measured 5.8 seconds (Figure 3).

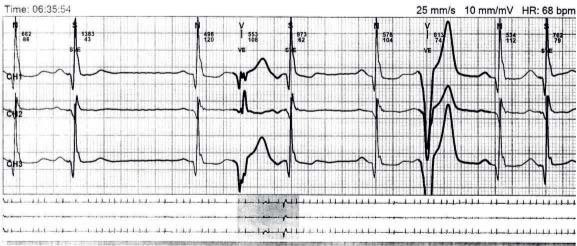

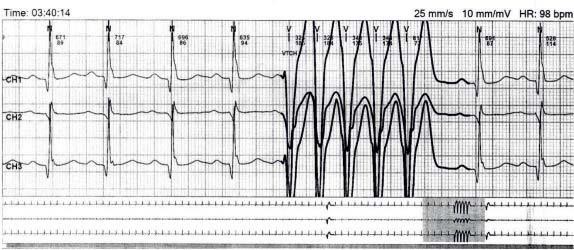

As the coronary artery disease was stable, with no argument for ongoing ischemia, down-titration of the beta-blocker was performed over the following weeks, which offered no significant benefit, as the patient continued to exhibit presyncopal episodes at doses as low as 50 mg/day, which led to the ultima-te interruption of the beta-blocker therapy. At this point, the Holter monitoring showed no more significant pauses but noted the occurrence of frequent bigeminated and trigeminated polymorphic prematu-re ventricular complexes and bouts of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (Figure 4, 5).

In this context, the symptomatic sinus node dys-function was interpreted as a consequence of the be-ta-blocker therapy, which was essential treatment for the coronary artery disease, both guideline-directed and clinically necessary. Therefore, permanent pacing was recommended to permit the continuation of the beta-blocker treatment, to maintain a tolerable ventri-cular rate and improve quality of life.

A double-chamber pacemaker was inserted, with DDD-R as the pacing mode of choice. The patient was discharged without peri-procedural complications and metoprolol treatment was reinstated.

Figure 1. Resting ECG showing sinus rhythm with a frequency of 89 bpm, inferior necrosis sequellae and flat T waves in the lateral leads.

Figure 2. Carotid arteriography demonstrating a 50-60% stenosis of the right internal carotid artery.

Figure 3. Holter monitoring showing 5.8 second pause while on 200 mg metoprolol succinate.

Figure 4. Holter monitoring showing polymorphic premature ventricular complexes (no beta-blocker therapy).

Figure 5. Holter monitoring showing a bout of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (no beta-blocker therapy).

DISCUSSION

Patients with extracranial cerebrovascular disease re-present a high-risk population with nearly double the incidence of syncope and increased cardiovascular mortality compared with those without cerebrovas-cular disease2.

It is reported that 1.4-4.1% of syncope can be at-tributable to cerebrovascular disease, though seldom in the absence of associated neurologic symptoms2. Although transient ischemia attacks (TIAs) related to carotid stenosis do not usually result in loss of con-sciousness, this may be the case in orthostatic TIAs, when associated with multiple stenosis of the carotid arteries1. This was not the case of our patient, whose non-critical unilateral stenosis was very unlikely to have caused the episodes of syncope, which prompted the search for a more plausible explanation.

The pathophysiology of SND is complex, with ei-ther a diffuse or localized arteriopathy as the morpho-logical substrate. This leads to a wide range of abnor-malities in the sinus node and atrial impulse formation and propagation3.

Beta-blockers are drugs commonly used in patients with cardiovascular disorders and have a wide ran-ge of guideline-directed indications for patients after myocardial infarction and in the case of chronic left ventricle systolic dysfunction. Patients with SND may often achieve an acceptable heart rate due to sym-pathetic stimulation and beta-blocker therapy may re-sult in significant bradycardia, even when administered in low doses. Therefore, while in some cases it might be reasonable to stop or decrease the dose of the incriminated drug, others, such as the patient presented above, should be managed with permanent pacing so that the essential pharmacologic therapy may be continued4.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

1. 2018 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope, Brignole M et al, European Heart Journal (2018) 39, 1883–1948.

2. Diagnostic utility of carotid artery duplex ultrasonography in the evaluation of syncope: a good test ordered for the wrong reason, Kadian-Dodov D; Papolos A; Olin JW, European Heart Journal – Cardiovascular Imaging (2015) 16, 621–625.

3. Biology of the Sinus Node and its Disease, Choudhury M; Boyett MR; Morris GM, Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev (2015) 4(1), 28-34.

4. 2018 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline on the Evaluation and Management of Patients With Bradycardia and Cardiac Conduction Delay, Ku-sumoto FM et al, Journal of the American College of Cardiology (2018).

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a