Catalin Pestrea1, Alexandra Gherghina1, Ramona Magdo-Mina1, Florin Ortan1

1 Unit of Intensive Cardiac Care, County Emergency Clinical Hospital, Brasov, Romania

Abstract: Myasthenia gravis (MG) is an autoimmune neuromuscular disease, characterized by specific autoantibodies directed against postsynaptic acetylcholine receptors. Although the disease affects primarily the skeletal muscles, involve-ment of other organs, including the heart, has been noted. The most common cardiac manifestations reported in MG are myocarditis and arrhythmias. The first line treatment consists in acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, of which pyridostigmine is the most effective. They increase the amount of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction. This results in an enhanced vagomimetic activity which may lead to serious bradyarrhythmias, including atrioventricular (AV) block. We present the case of a 60-years old patient with known myasthenia gravis under pyridostigmine treatment, which was admitted to our hospital for fatigue and dizziness. The presenting ECG showed sinus rhythm with 2:1 atrioventricular block. We interpre-ted the case as a symptomatic AV block induced by pyridostigmine at a dose necessary to control the myasthenia gravis symptoms and we decided to implant a permanent dual chamber cardiac pacemaker. In order to minimize the complications associated with long-term ventricular pacing, we opted for permanent His bundle pacing which resulted in atrioventricular resynchronization with normal ventricular electrical activation. The six months follow-up showed optimal stable pacing and sensing parameters and no decline in ejection fraction.

Keywords: myasthenia gravis, pyridostigmine, AV block, His bundle pacing.

INTRODUCTION

Myasthenia gravis is an autoimmune neuromuscular disease that affects primarily skeletal muscles, but in some cases both the disease and the treatment could involve the heart leading to serious complications like myocarditis and rhythm disturbances.

CASE REPORT

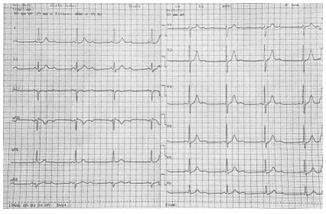

A 60 years old patient with known myasthenia gravis under pyridostigmine treatment was admitted to our hospital for fatigue and dizziness. The presenting ECG showed sinus rhythm with 2:1 atrioventricular (AV) block (Figure 1).

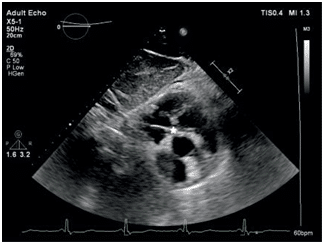

The lab tests were unremarkable and the echocar-diography showed normal contractility and a mild mi-tral regurgitation.

The patient has recently increased the pyridostigmi-ne dose from 15 mg bid to 30 mg bid due to diplopia occurrence and was at that moment asymptomatic in regard to myasthenia gravis.

We interpreted the case as a symptomatic 2:1 AV block induced by pyridostigmine at a dose necessary to control the myasthenia gravis symptoms and we decided to implant a permanent dual chamber cardiac pacemaker.

In order to minimize the complications associated with long-term ventricular pacing, we opted for per-manent His bundle pacing.

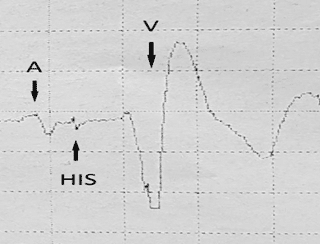

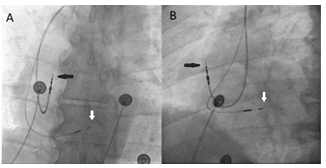

This procedure has been widely described elsewhe-re1. Briefly, after gaining venous access, with the support of the C315 His sheath (Medtronic, Minneapolis) to reach the septal AV junction, we used the 3830 Select Secure lead (Medtronic, Minneapolis) to map for the His signal and when a good His signal was recorded (Figure 2), the lead was screwed in at that site (Figure 3). A selective His bundle capture was achieved with a threshold of 1 V/1 ms and a sensing value of 3 mV. Finally, an atrial lead was placed in the right atrial appendage.

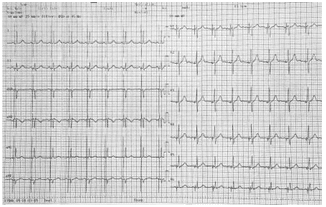

The post-procedural ECG showed sinus rhythm with atrial synchronized paced QRS complexes with a morphology identical to the native ones (Figure 4).

The patient was discharged the next day. The 1 month, 3 months and 6 months follow-ups showed stable pacing and sensing thresholds (1 V/1 ms and 3 mV respectively), the patient being completely asymp-tomatic with good exercise tolerance.

Figure 1. ECG at presentation showing sinus rhythm with 2:1 AV block.

Figure 2. Intracardiac electrogram during mapping showing a good His bundle signal. (A=atrial electrogram; HIS=His bundle electrogram, V=ventricular electrogram).

DISCUSSION

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is an autoimmune disease in which autoantibodies directed against postsynaptic acetylcholine receptors cause defective neuromuscular signal transmission, thus resulting in skeletal muscle weakness2.

Although the disease affects primarily the skeletal muscles, involvement of other organs, including the heart has been noted.

The most common cardiac manifestations reported in MG are myocarditis and arrhythmias3.

Antibodies against acetylcholine receptors do not bind to myocytes. On the other hand, striational an-tibodies (anti-titin, anti-ryanodine receptor and anti Kv 1.4 antibodies) attack the heart muscle and this appears to be the cause of myocardial inflammation4.

Also, the presence of thymoma associated with MG was shown to be an important prognostic factor for myocarditis because 97% of these patients have stria-tional antibodies5.

So far, no definite direct effect of MG on the cardiac conduction system could be determined.

Apparently, most of the fl uctuations in heart rate are due to autonomic imbalance6. But, in patients with anti Kv 1.4 antibodies, more serious arrhythmias like ventricular tachycardias, complete AV block and sud-den cardiac death have been described.

One of the mainstays of MG treatment are acetyl-cholinesterase inhibitors, of which pyridostigmine is the most effective. The mechanism of action is an in-crease of acetylcholine concentrations at the neuro-muscular junction and thus an increased acetylcholine receptor stimulation7.

This results in an enhanced vagomimetic activity which could lead to bradycardia or AV block, beca-use the AV node is richly innervated with cholinergic neurons.

Although acute electrophysiological studies show-ed no significant prolongation of AV node conduction after pyridostigmine administration8, there are several case reports in the literature describing either sinoa-trial or AV block leading to hospitalization and even cardiac pacing in patients receiving this treatment9,10.

In our case, the patient had no thymoma and his AV conduction abnormalities appeared after the increase in pyridostigmine dose for diplopia.

For these reasons, we interpreted the case as a drug related symptomatic second degree AV block and be-cause we didn’t want to withdraw the medication due to concern of MG symptoms relapse, we decided to implant a permanent dual chamber pacemaker.

When considering permanent cardiac pacing, a ca-reful balance must be made between the benefits of atrioventricular resynchronization and the deleterious effects of long term right ventricular pacing.

One of the most serious adverse effects of a high right ventricular pacing burden (especially more than 40% of the time) is a decrease in left ventricular systo-lic function, the so called pacing induced cardiomyo-pathy. This is usually defined as a drop in ejection fraction of more than 10% resulting in a value below 50% and it is encountered in approximately 20% of the paced patients11.

Another potential problem associated with the pre-sence of a right ventricle lead is an increase in tricus-pid valve dysfunction, which could lead in time to right heart failure and systemic congestion12.

Fortunately, in the last decade, to overcome these issues, new forms of physiological pacing have been studied and His bundle pacing emerged as the most physiological one.

The advantages of this kind of cardiac pacing are obvious – the electrical activation of both ventricles is synchronous because it uses the intrinsic conduction system and usually the lead is placed on the atrial side of the tricuspid valve (Figure 5), which prevents tricus-pid regurgitation worsening.

Therefore, using a dual chamber pacemaker, one can achieve atrioventricular resynchronization, thus fully optimizing ventricular filling and the cardiac out-put, without the long term deleterious effect of right ventricular pacing13.

With the recent advances in technology and the la-test lead delivery systems, a success rate of up to 90% in His bundle pacing has been demonstrated with little adverse effects14.

Depending on the QRS morphology, after His bundle pacing, two types of response have been de-scribed: selective His bundle pacing, in which there is only His bundle capture and the resulting QRS and T wave are identical to the native ones and non-selective His bundle pacing, in which there is both local capture in the basal septal myocardium and His bundle captu-re with a resulting narrow QRS with a “pseudo delta wave” appearance and a modifi ed T wave15.

There are several studies which show no significant hemodynamic differences between the two respon-ses16.

Several potential issues with His bundle pacing co-uld occur, like an increasing pacing threshold, atrial oversensing and ventricular undersensing.

In our case, we achieved selective His bundle pacing at a low threshold (1 V/1 ms) and with decent sensiti-vity (3 mV), which remained stable over time.

Although the patient was 100% ventricular paced, there was no decrease in systolic function at follow-up.

In this way, we were able to keep the necessary do-ses of pyridostigmine to control the myasthenia gravis symptoms while maintaining the normal electrical ac-tivation of the heart.

Figure 3. Posteroanterior (A) and left anterior oblique (B) chest x-ray images showing final lead position (black arrow – atrial lead; white arrow – His bundle lead).

Figure 4. Postprocedural ECG showing selective His bundle pacing: sinus rhythm with atrial synchronized paced QRS complexes with a morphology identical to the native ones.

Figure 5. Subcostal short-axis view echocardiography image showing His bundle lead tip fixed on the atrial side of the tricuspid valve (white star).

CONCLUSION

In this subset of patients with drug-related bradyar-rhythmias, His bundle pacing is an option to effectively restore the normal electrical cardiac activation, while continuing the necessary medical treatment.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

1. Dandamudi, G., & Vijayaraman, P. (2016). How to perform perma-nent His bundle pacing in routine clinical practice. Heart Rhythm, 13(6), 1362–1366.

2. Gilhus, N. E. (2016). Myasthenia Gravis. New England Journal of Medicine, 375(26), 2570–2581. doi:10.1056/nejmra1602678.

3. Shivamurthy, P., & Parker, M. W. (2014). Cardiac manifestations of myasthenia gravis: A systematic review. IJC Metabolic & Endocrine, 5, 3–6.

4. Suzuki, S., Utsugisawa, K., Nagane, Y., & Suzuki, N. (2011). Three Types of Striational Antibodies in Myasthenia Gravis. Autoimmune Diseases, 2011, 1–7.

5. Guglin M, Campellone JV, Heintz K, et al. Cardiac disease in myas-thenia gravis: a literature review. J Clin

6. Neuromuscul Dis. 2003;4(4):199–203.

7. Hamed SA, Mohamad KO, Adam M. Cardiac autonomic function in patients with myasthenia gravis: analysis of the heart-rate variability in the time-domain. Neuroimmunol Neuroinflammation 2015;2(1): 21-5.

8. Khan, M. S., Tiwari, A., Khan, Z., Sharma, H., Taleb, M., & Ham-mersley, J. (2017). Pyridostigmine Induced Prolonged Asystole in a Patient with Myasthenia Gravis Successfully Treated with Hyoscya-mine. Case Reports in Cardiology, 2017, 1–4.

9. L.I. Zimerman, A. Liberman, R.R.T. Castro, J.P. Ribeiro and A.C.L. Nóbrega. Acute electrophysiologic consequences of pyridostigmine inhibition of cholinesterase in humans. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research (2010) 43: 211-216.

10. Sarmad Said, Chad J. Cooper, Haider Alkhateeb, Sherif Elhanafi, Jorge Bizet, Sucheta Gosavi, Zainul Abedin. Pyridostigmine-induced high grade SA-block in a patient with myasthenia gravis. Am J Case Rep 2013; 14:359-361.

11. Chaucer, B., Whelan, D., & Lamichhane, D. (2018). Pyridostigmine induced heart block requiring ICU admission. Journal of Community Hospital Internal Medicine Perspectives, 8(5), 283–284.

12. Khurshid, S., Epstein, A. E., Verdino, R. J., Lin, D., Goldberg, L. R., Marchlinski, F. E., & Frankel, D. S. (2014). Incidence and predictors of right ventricular pacing-induced cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm, 11(9), 1619–1625.

13. Ebrille, E., Chang, J. D., & Zimetbaum, P. J. (2018). Tricuspid Valve Dysfunction Caused by Right Ventricular Leads. Cardiac Electro-physiology Clinics, 10(3), 447–452.

14. Abdelrahman, M., Subzposh, F. A., Beer, D., Durr, B., Naperkowski, A., Sun, H., Oren J.W., Dandamudi G., Vijayaraman, P. (2018). Clini-cal Outcomes of His Bundle Pacing Compared to Right Ventricu-lar Pacing. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 71(20), 2319–2330.

15. Francesco Zanon, Kenneth A. Ellenbogen, Gopi Dandamudi, Parik-shit S. Sharma, Weijian Huang, Daniel L. Lustgarten, Roderick Tung, Hiroshi Tada, Jayanthi N. Koneru, Tracy Bergemann, Dedra H. Fa-gan, John Harrison Hudnall, and Pugazhendhi Vijayaraman10. (2018). Permanent His-bundle pacing: a systematic literature review and me-ta-analysis. EP Europace. doi:10.1093/europace/euy058.

16. Vijayaraman, P., Dandamudi, G., Zanon, F., Sharma, P. S., Tung, R., Huang, W., Koneru J., Tada H., Ellenbogen K.A., Lustgarten, D. L. (2018). Permanent His bundle pacing: Recommendations from a Multicenter His Bundle Pacing Collaborative Working Group for standardization of definitions, implant measurements, and follow-up.Heart Rhythm, 15(3), 460–468.

17. Dominik Beer, Parikshit S. Sharma, Faiz A. Subzposh, Ange-la Naperkowski, Grzegorz Marcin Pietrasik, Brendan Durr, Maria Qureshi, Ragesh Panikkath, Mohamed Abdelrahman, Brent A. Wil-liams, Jillian L. Hanifin, Ryan Zimberg, Kelly Austin, Brooke Macuch, Richard G. Trohman, Erin A. Vanenkevort, Gopi Dandamudi and Pugazhendhi Vijayaraman (2019). Clinical Outcomes Of Selective Versus Nonselective His Bundle Pacing. JACC: Clinical Electrophysi-ology. doi:10.1016/j.jacep.2019.04.008.

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a