Mihaela Anton1, Aura Popa1, Carmen Ginghina1,2

1 “Prof. Dr. C.C.Iliescu” Emergency Institute for Cardiovascular Diseases, Bucharest, Romania

2 “Carol Davila” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania

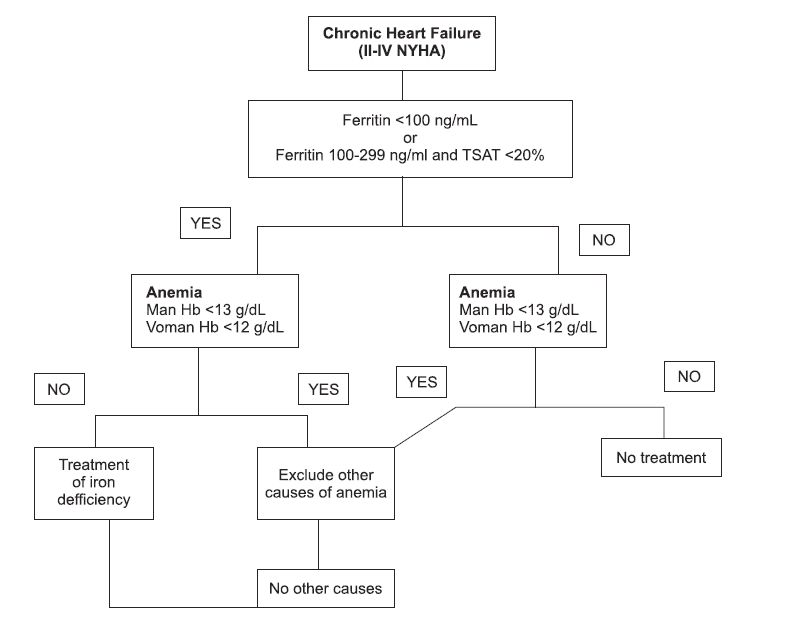

Abstract: Iron deficiency, defined as a value of ferritin level under 100 ng/ml or between 100 and 299 ng/ml, when the transferrin saturation is <20%, represents an important comorbidity in heart failure, its prevalence being directly correlated with the increase in the NYHA scale. Despite this fact, it is frequently neglected. Moreover, it has been observed that iron deficit is an important predictor of morbidity and mortality, even in the absence of anemia.

Keywords: iron deficiency, anemia

INTRODUCTION

Iron deficiency represents an important comorbidity in heart failure, however it is frequently neglected. It has been proved that iron defciency is common in one of two patients with chronic heart failure, its prevalence being directly correlated with the increase in the NYHA scale1-3. Iron defi ciency is defined as a value of ferritin level under 100 ng/ml or between 100 and 299 ng/ml, if the transferrin saturation is <20%2. Moreover, it has been observed that iron deficit is an important predictor of morbidity and mortality, even in the absence of anemia4. The following algorithm is recommended to diagnose iron defi ciency in chronic heart failure1,4. Therefore, the 2016 Heart Failure ESC Guide recommends to investigate iron parameters in all patients with chronic heart failure and to treat iron deficiency with ferric carboxymaltose regardless of the presence of anemia5,6.

CASE PRESENTATION

We present the case of a 63 years old woman, without any cardiovascular risk factors, diagnosed with dilated cardiomyopathy and severe systolic dysfunction of left ventricle (LVEF=15%), who came to the hospital for symptoms of congestive heart failure (minimal effort dyspnea, large amount of ascites fluid and severe peripheral edema). The patient was diagnosed with dilated cardiomyopathy 6 years ago, when she presented to the hospital for medium effort dyspnea and abnormal, high rate heartbeats. In order to exclude an ischemic ethiology of the dilated cardiomyopathy, the patient underwent a coronary angiography and no lesions of the coronaries were discovered. In addition, in order to evaluate the possibility that the cardiac dysfunction was secondary to viral myocarditis we performed viral markers for hepatitis C, hepatitis B, HIV, CMV, EBV, Toxoplasma and Treponema pallidum, which were all negative. Acording to Heart Failure ESC Guide5, in order to prevent sudden cardiac death, and because of the fact that on the Holter ECG recording there were observed episodes of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia, a cardioverter-defibrillator implant (I.C.D.) has been performed. Clinical examination revealed, BP=100/60 mmHg, HR=70/min, rhythmic cardiac sounds, systolic murmur (IV/IV) in the mitral and tricuspid positions, bibasilar crackles, firm and painful hepatomegaly, turgescent jugular veins, large amount of ascites fluid and severe peripheral edema. On the electrocardiogram, we observe sinus rhythm and first- degree atrioventricular block. Blood tests reveal incresed BNP (1940.7 pg/ml), moderate kidney dysfunction, cholestasis syndrom (total bilirubin=3,06 mg/dl, direct bilirubin=1.73 mg/dl, GGT=205 u/l), iron deficency (total iron 41 mg/dl, ferritin 34.5 ng/ml), and no anemia (Hb=13.1 g/dl). Transthoracic ecocardiography showed the aspect of biventricular dilated cardiomyopathy, with severe systolic dysfunction due to diffuse hypokinesia (LVEF 15%), severe biatrial dilation, severe mitral and tricuspid regurgitation, and moderate secondary pulmonary hypertension (estimated sPAP at 50 mmHg).

Figure 1. Relationship between cardiovascular complications and depression.

DISCUSSIONS

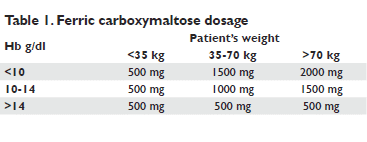

The patient received treatment with high dose loop diuretic, in continuous iv administration, with slow response of the diuresis and slow regression of hidrosalin retention. In addition, in accordance with 2016 ESC Guide of Heart Failure5, 1000 mg of ferric carboxymaltose were administered, with very good tolerance. The dose needed to correct iron deficiency was calculated

according the following table4,6. On discharge, we can observe an improvement in the patient’s symptomatology, at the six minutes walk test, she managed to cover 252 m. Three months later, the clinical evaluation showed an increase in the patient’s tolerance to effort, at the six minutes walk test, managing to cover with 150 m more than the previous examination. Additionally, we can observe the correction of the ferritin level and a normal value of the hemoglobin. Subsequently, it is recommended to evaluate iron parameters 1-2 times a year, whether alterations in the symptomatology appear or if the hemoglobin level decreases9. The particular aspects of the case are:

• the presence of dilated cardiomyopathy with severe systolic dysfunction in a woman without cardiovascular risk factors, with a rapid evolution.

• maintaining sinus rhythm despite the severe atrial dilation.

• the improvement of the symptomatology and effort capacity after the correction of the iron deficiency.

CONCLUSION

To sum up, we emphasize the importance of investigating iron parameters in all patients diagnosed with chronic heart failure, regardless of the presence of anemia. Even though this may seem as a minor aspect in the long list of investigations needed for diagnosis, it has a significant impact on the quality of life of patients suffering from chronic heart failure.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

1. Anker SD, Colet JC, Filippatos G, et al., Rationale and design of Ferinject Assessment in patient with Iron defi ciency and chronic Heart Failure (FAIR-HF) study: a randomised, placebo controlled study of intravenous iron supplementation in patients with and without anaemia- Eur J Heart Fail 2009;11:1084-91.

2. Groenveld HF, Januzzi JL, Damman K, et al., Anemia and mortality in heart failure patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis, J Am Col Cardiol 2008;52:818-27.

3. Van Veldhuisen DJ, Anker SD, Ponikowski P, et al, Anemia and iron defi ciency in heart failure: mechanisms and therapeutic approaches, Nat Rev Cardiol 2011;8:485-93.

4. Stefan D. Anker, Josep Comin Colet, Gerasimos Filippatos, et al., Ferric Carboxymaltose in Patients with Heart Failure and Iron Defi ciency- N Engl J Med 2009; 361:2436-48.

5. Piotr Ponikowski, Adriaan A. Voors, Stefan D. Anker et al, 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure – Web Addenda The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) – European Heart Journal 6. Ewa A. Jankowska, Jolanta Malyszko, Hossein Ardehali et al., Iron status in patients with chronic heart failure- European Heart Journal (2013) 34, 827–834

7. Maeder MT, Khammy O, dos Remedios C et al., Myocardial and systemic iron depletion in heart failure implications for anemia accompanying heart failure, J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:474–480.

8. Jankowska EA, Rozentryt P, Witkowska A, Nowak J et al., Iron deficiency predicts impaired exercise capacity in patients with systolic chronic heart failure, J Card Fail 2011;17:899–906.

9. Isbrand T. Klip, Josep Comin-Colet, Adriaan A. Voors, et al., Iron deficiency in chronic heart failure: An international pooled analysis, Am Heart J 2013;165:575-582.

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a