Larisa Anghel1,2, Cristina Prisacariu1,2, Amin Bazyani1,2, Liviu Macovei1,2

1 „Grigore T. Popa” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Iasi, Romania

2 „Prof. Dr. George I. M. Georgescu” Institute of Cardiovascular Diseases, Iasi, Romania

Abstract: Objectives – Severe arrhythmias can appear as a complication in acute myocardial infarction with ST segment elevation (STEMI) and can be a cause of higher in-hospital mortality. The aim of our paper was to show if the arrhythmias can explain study the higher mortality in women with STEMI. Methods – We study the arrhythmic complications, both tachyarrhythmias and bradyarrhythmias in female with STEMI admitted in the Cardiovascular Diseases Institute ,,Prof. Dr. George I. M. Georgescu” Iaşi between 1 September 2011 and 1 September 2012. Patients enrolled in the study were aged between 29 and 90 years old, 207 women and 445 men, and the mean age of the female population was 68.20 ± 10.8 years. The arrhythmias were diagnosed retrospectively based on the existing electrocardiograms. Results – Anterior myocardial infarction was the most common STEMI localization in the analyzed population, regardless of sex, but more women had anterior myocardial infarction than men, with a statistically significant difference: p = 0.021. Ventricular tachycardia appeared as a complication of myocardial infarction in 5.4% of subjects, 4.3% of women and 5.8% of males: p = 0.142. In the first 48 hours, ventricular fibrillation occurred at 2.9% of female and 5% of males, and after this limit, it was more common in the female group(1.9% of females and 0.4% of males, p <0.001). Atrial fibrillation occurred during hospitalization in 5.75% of pa-tients, 7.7% of women and 3.8% of males, p = 0.048. Total atrioventricular block as a complication of myocardial infarction, was more frequent in men (5.3% versus 3.4%), p = 0.441. Total mortality rate during the hospitalization was 5.67%, and it was much among women, compared to men. Conclusions – The results of our study show that women had more frequent than men atrial fibrillation and ventricular fibrillation developed 48 hours after admission. This can be explained by the more frequent anterior wall involvement in myocardial infarction in women from our study. The higher mortality can be explained mainly by the higher prevalence of anterior wall myocardial infarction and the older age of women comparative with men, more severe arrhythmias being a consequence of these facts.

Keywords: arrhythmia, myocardial infaction, women, complications, mortality.

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular diseases and, in particular, atheroscle-rotic coronary artery disease, have been considered, up until a few decades ago, as a disease of male popu-lation. Subsequent studies, which included more and more women, however, indicated that cardiovascu-lar diseases also affect women, in whom the vascu-lar involvement manifests with a delay of about 7-10 years1,2.

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death among women regardless of race or ethnicity. Appro-ximately half of these deaths are due to coronary artery disease. Several studies have reported higher in-hospital mortality in female with ST-segment ele-vation acute myocardial infarction (STEMI) compared to males3-6.Over time, several hypotheses have been formulated to explain the higher in-hospital mortality in female STEMI patients, such as the more advanced age, presence of more comorbidities, longer ischemic time, or the suboptimal use of reperfusion strategies.

It has not yet been established whether female gen-der, through the biological and sociocultural differen-ces it involves, is itself a risk factor for early in hospital mortality in patients with STEMI.

Arrhythmic complications may develop in about 90% of patients who have an acute myocardial infarc-tion (AMI) during or immediately after the event, and in 25% of patients, such rhythm abnormalities appear within the first 24 hours. Many of the severe arrhyth-mias, which may complicate the evolution of STEMI, occur before hospitalization and they can result in sudden death or reduced cardiac output. The risk of serious arrhythmias, such as ventricular fi brillation, is greatest in the first hour of patients with STEMI. In non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) this risk is lower7.

The mechanism of arrhythmic complication in myo-cardial infarction is hypoxia, electrolyte imbalances and a generalized autonomic dysfunction that cause an enhanced automaticity of the myocardium and con-duction system all on top of a damaged myocardium that acts as substrate for re-entrant circuits.

Premature ventricular contractions, accelerated idioventricular rhythm, and non-sustained ventricular tachycardia are of no prognostic value and require no treatment, except correction of electrolyte disturban-ces and acidosis when is the case. Most episodes of ta-chycardia and ventricular fibrillation occur within the first 48 hours of the onset of the infarction and are treated immediately by an external electrical shock8.

Current guidelines do not recommend prophylactic antiarrhythmic therapy for the prevention of primary ventricular fibrillation9,10.

The incidence of ventricular fi brillation may be de-creased by early myocardial revascularization, by the early administration of intravenous betablockers and by the correction of hypokalemia and hypomagnese-mia.

Factors precipitating supraventricular arrhythmias, especially fl utter and atrial fibrillation, are: excessive sympathetic stimulation, ventricular dysfunction, atrial infarction, hypokalemia, pericarditis and hypoxia. The occurrence of atrial fi brillation is associated with an unfavorable short and long term prognosis, and with an increased risk of systemic embolization11,12.

If arrhythmia causes angina or hemodynamic de-gradation, electrical cardioversion should be used. In stable patients, in the absence of contraindications, a beta-blocker should be given.

Bradyarrhythmias can be induced by an excessive vagal stimulation or may be caused by ischemic injury of the tissue. Intra-ventricular conduction disorders occur in 10-20% of patients, and atrioventricular blocks can be seen in 6-14% of patients with STEMI13,14. These complications increase the risk of death because they are generally associated with large areas of infarction.

METHODS

The aim of our study was to detect the particularities of arrhythmic complications in female with STEMI. In order to resolve the proposed goal, we made a re-trospective observational study, which included pati-ents with acute myocardial infarction with ST segment elevation, admitted to the Cardiology Clinic of the Cardiovascular Diseases Institute ,,Prof. Dr. George I. M. Georgescu”, Iaşi between 1 September 2011 and 1 September 2012.

Arrhythmic complications, both tachyarrhythmias and bradarrhythmias, have been diagnosed based on the existing electrocardiograms. Between 1 Septem-ber 2011 and 1 September 2012, in the Cardiology Clinic were hospitalized 652 patients with acute myo-cardial infarction who met the inclusion criteria: 207 women and 445 men. Patients enrolled in the study were aged between 29 and 90 years old, with a mean age of the female population of 68.20 ± 10.8 years.

RESULTS

Electrocardiographic localization of the myocardial infarction

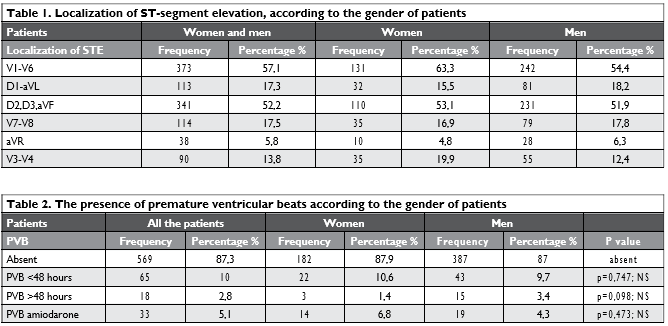

Anterior myocardial infarction was the most com-mon STEMI localization in the analyzed population, regardless of gender, but more women had anterior myocardial infarction, with a statistically significant di-fference: p = 0.021. The second location, as frequency, was inferior myocardial infarction and the incidence was also higher in women: p = 0.927. The posteri-or and lateral myocardial infarction was diagnosed in less than one-fifth of patients included in the study, regardless their sex (Table 1).

Premature ventricular beats

Premature ventricular beats (PVB) complicated myo-cardial infarction in 12.8% of patients, without sta-tistically significant differences (p = 0.815) between women (12%) and men (13.1%). In the first 48 hours, ventricular arrhythmia, although insignificantly statisti-cally, was more common in women. After 48 hours, their frequency decreased significantly in both groups, but the percentage of men exceeded the proportion of women.

The severity of this arrhythmia was assessed only based on the need to initiate antiarrhythmic drugs (amiodarone). More women received amiodarone treatment, but the difference was not statistically sig-nificant (Table 2).

Ventricular tachycardia

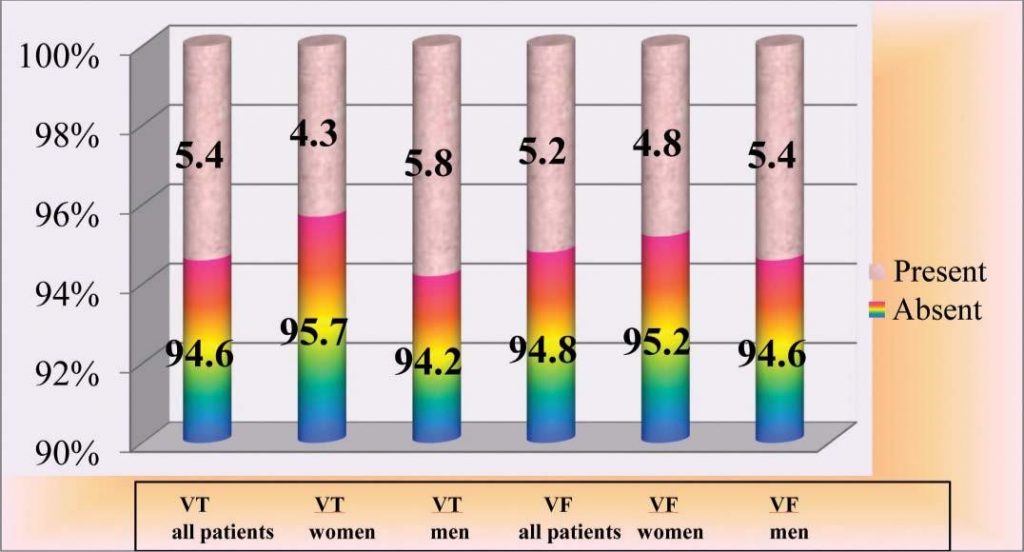

Ventricular tachycardia was present in 5.4% of sub-jects, representing 4.3% of women and 5.8% of ma-les: p = 0.142. In order to treat it, external electrical shock was required in hemodinamically unstable pati-ents (1.2%), the others received antiarrhythmic drugs (4.2%). Antiarrhythmic drugs were administered to 2.9% of women and 4.7% of men, but the difference between the two groups was not statistically signifi-cant: p = 0.342. External electrical shock was needed to solve the ventricular tachycardia in more women (1.4%) than men (1.1%), with a statistically signifi cant difference: p <0.001.

Ventricular fibrillation

Ventricular fibrillation appeared in 6.4% of patients (4.8% of women and 5.4% of men, p= 0.438, without a statistically significant difference). In the first 48 hours, this ventricular arrhythmia occurred at 2.9% of female and 5% of males (p = 0.375). After the first 48 hours, the incidence of this complication decreased signifi-cantly, but was more common in the female group (1.9% of females and 0.4% of males, p <0.001) (Figure 1).

Atrial fibrillation

At the time of admission in our clinic, the electrocardi-ogram already showed atrial fibrillation in 72 patients (11.04%), with no statistically significant difference in the proportion of women (14.5%) and men (9.4%); p = 0.811. Atrial fibrillation occurred during hospitalization in 5.75% of patients (7.7% of women and 3.8% of male, p = 0.048). For all women who developed arrhythmia during hospitalization, this occurred after the first 24 hours. On the contrary, in men, atrial fibrillation appeared especially in the first day (2.02%), and in a smaller percentage (1.79%) in the next days.

Figure 1. The presence of ventricular tachycardia (VT) and fibrillation (VF) in patients included in the study.

Right bundle branch block

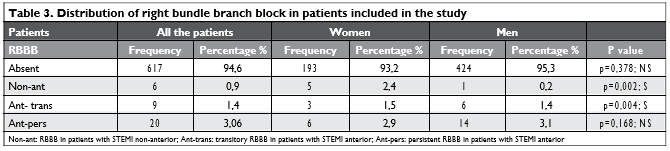

The right bundle branch block (regardless of the loca-tion of ST segment elevation) was recorded at 5.4% of all the patients, without statistically signifi cant di-fferences between the two genders: it was diagnosed in 6.7% of women and in a lower percentage of men, only 4.7% (p = 0.592) (Table 3).

Atrioventricular conduction disorders Atrioventricular conduction disorders occurred at 10.5% of patients, with no statistically significant diffe-rence between the two genders although the propor-tion of men was higher (11.1% versus 9.2%, p = 0.841).

Grade I atrioventricular block was detected in a higher percentage of men (4.9%), compared to only 2.4% of women, but the difference was not statistically significant: p = 0.267.

Grade II atrioventricular blocks were also obser-ved more frequently in men (3.3%); only 1.4% of the female group members had this atrioventricular con-duction disorder, but the difference between the two sexes did not meet the statistical significance criteria: p = 0.07. The proportion of women with acute coro-nary syndrome complicated by a total atrioventricular block was higher than that of men (5.3% versus 3.4%), although in this case the difference was not statistically significant: p = 0.441.

Death during hospitalization

Total mortality rate during the hospitalization was 5.67%, and it was higher among women, 30 patients, compared to men, where only a number of 7 men died, p = 0.764. The main causes of death were: cardiogenic shock, electromechanical dissociation, mecha-nical complications and asystole. Analyzing the correlation between different variables considered as particularities of the female population studied and the risk of death during hospitalization, we discovered that there is a high statistically significant correlation between older age and the risk for death. This association was also confirmed by the Pearson correlation (r = 0.210 for p <0.01) and ANOVA test (p <0.01). Also, low left ventricular ejection fraction, cardiogenic shock, left ventricular thrombosis, bra-dyarrhythmias requiring temporary electrical cardiostimulation and ventricular fibrillation were other factors that were associated with an increase in ho-spital mortality in the case of women, but without a statistically significant correlation.

DISCUSSIONS

The mean age of women included in the study was 68.2 years, with almost 8 years higher than that of males, 60.67 years, with a statistically significant diffe-rence (p <0.001). These data are concordant with those from the literature, and the fi rst episode of acu-te coronary syndrome occurs after menopause and is delayed by about 6-10 years in women than in men15,16. The temporal shift in the incidence of acute coronary syndrome in women is most likely due to the protec-tive effect of endogenous estrogens17.

In our study, the most frequent localization of myo-cardial infarction, both in women and men, was the anterior one, followed by the inferior localization. Data from the literature about the association betwe-en location of the myocardial infarction and gender, are few and inconsistent17-19. The gender distribution analysis revealed a greater proportion of posterior (inferior) and lateral/apical localizations in men and a higher incidence of anterior and inferior myocardial infarction in women. The highest percent differences were observed for ST segment elevation in V1-V6 and ST segment elevation in aVR, both in favor of women. The higher incidence of previous myocardial infarction in women was also reported by other studies, but its role as an independent risk factor for adverse progno-sis was not confi rmed19,20.

Most patients included in the study were in sinus rhythm at admission. With statistically significant di-fferences, the percentage of women with atrial fibrilla-tion was higher than in men. The higher frequency of atrial fibrillation on the initial electrocardiogram in females was also observed in other studies, but with smaller percentages and undetectable predictive va-lue for evolution17. In our study, women had more frequent ventricular tachycardia than males, although the low percentage of patients with this cardiac ar-rhythmia might disturb this conclusion.

In our study, premature ventricular beats occurred during hospitalization with a higher prevalence (but not statistically signifi cant) among the male populati-on. If during the first 48 hours premature ventricular beats were reported in several women, after the first two days they were more common in males (the gen-der gap was not statistically signifi cant). In both groups the incidence of this arrhythmia decreased from day 3, and the decrease was more signifi cant in the female group. This evolution of premature ventricular beats could be correlated with the initiation of treatment with amiodarone in a higher percentage of women than men. Several studies have shown that ventricular tachycardia and/or ventricular fibrillation have been associated with an increased risk of late or early ho-spital death in patients with STEMI treated with fibri-nolytic medication21-23. However, the prognostic signi-ficance of these ventricular arrhythmias after primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in patients with STEMI was rarely analyzed. The HORIZONS-AMI trial evaluated the incidence, clinical correlation and evolution of VT/FV in the hospital after PCI. Published results suggest that these arrhythmias occur after in-terventional therapy and prior to discharge to appro-ximately 5% of patients with STEMI, most in the first 48 hours. Independent predictors for their occurren-ce were Killip >1 at presentation, presence of coro-nary thrombus, absence of diabetes mellitus and beta blocking medication, as well as a longer symptom-PCI time22. There was no correlation between these ven-tricular arrhythmias and the increased risk of major complications over a three-year follow-up, except for a higher risk of stroke. The variables analyzed were not reported in either the sex of the patients or the therapy applied to the rhythm disorders.

In our study, ventricular tachycardia complicated the myocardial infarction in 5.4% of subjects, and it was more common in men, but the 1.5% difference from women was not statistically significant. Ventricu-lar fibrillation occurred in 6.4% of the patients inclu-ded in this study, more commonly in males, but with only 0.6% difference (without statistical signifi cance) compared to women. After the first 48 hours, the frequency dropped signifi cantly among both women (1.9%) and men (0.4%) and the 1.5% difference in favor of women exceeded the statistical significance. Atrioventricular conduction disorders, were more commonly seen in men, with no statistically significant difference with women.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of our study show that women had more frequent than men atrial fibrillation and ventricular fibrillation developed 48 hours after admission. This can be explained by the more frequent anterior wall involvement in myocardial infarction in women from our study. The higher mortality can be explained ma-inly by the higher prevalence of anterior wall myo-cardial infarction and the older age of women com-parative with men, more severe arrhythmias being a consequence of these facts.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

1. World Health Organization. Prevention of cardiovascular disease: Guidelines for assessment and management of cardiovascular risk. Geneva, WHO, 2007.

2. World Health Organization. Global status report on noncommuni-cable diseases 2010. Geneva, WHO, 2010.

3. Hillis LD, Smith PK, Anderson JL, Bittl JA, Bridges CR, Byrne JG, Cigarroa JE, Disesa VJ, Hiratzka LF, Hutter AM Jr., Jessen ME, Keeley EC, Lahey SJ, Lange RA, London MJ, Mack MJ, Patel MR, Puskas JD, Sabik JF, Selnes O, Shahian DM, Trost JC, Winniford MD. 2011 ACCF/AHA Guideline for Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/Ameri-can Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines Circulation 2011;124(23):652-735.

4. Claassen M, Sybrandy KC, Appelman YE. Gender gap in acute coro-nary heart disease: myth or reality? World J Cardiol2012;4:36-47.

5. Kang SH, Suh JW, Yoon CH. Sex differences in management and mortality of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (from the Korean Acute Myocardial Infarction National Registry). Am J Cardiol 2012;109:787-793.

6. Milcent C, Dormont B, Durand-Zaleski I. Gender differences in hos-pital mortality and use of percutaneous coronary intervention in acute myocardial infarction: microsimulation analysis of the 1999 nationwide French hospitals database. Circulation 2007;115:833-839.

7. Dayan V, Soca G, Parma G, Mila R. Does early coronary artery by-pass surgery improve survival in non-ST acute myocardial infarction? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2013;17(1):140-142.

8. Campbell RW, Murray A, Julian DG. Ventricular arrhythmias in first 12 hours of acute myocardial infarction: natural history study. Br Heart J 1981;46:351-357.

9. Mac Mahon S, Collins R, Peto R. Effects of prophylactic lidocaine in suspected acute myocardial infarction: An overview of results from the randomized, controlled trials. JAMA 1988;260:1910-1916.

10. Alexander JH, Granger CB, Sadowski Z, et al, for the GUSTO-I and GUSTO-IIb investigators: Prophylactic lidocaine use in acute myocardial infarction: incidence and outcome from two international tri-als. Am Heart J 1999;137:799-805.

11. Pedersen OD, Bagger J, Kober L. TRAndolapril Cardiac Evaluation (TRACE) study group: The occurrence and prognostic signifi cance of atrial fibrillation/fl utter following acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 1999;20:748-754.

12. Pizzetti F, Turazza FM, Franzoni MG. Incidence and prognostic signif-icance of atrial fi brillation in acute myocardial infarction: the GISSI-3 data. Heart 2001;86:527-532.

13. Berry NC, Kereiakes DJ, Yeh RW, Steg PG, Cutlip DE, Jacobs AK, Abbott JD, Hsieh WH, Massaro JM, Mauri L. Benefit and risk of pro-longed DAPT after coronary stenting in women. Circ Cardiovasc Interv2018;11:e005308.

14. Yu J, Mehran R, Baber U, Ooi SY, Witzenbichler B, Weisz G, Rinaldi MJ, Neumann FJ, Metzger DC, Henry TD, Cox DA, Duffy PL, Maz-zaferri EL Jr, Brodie BR, Stuckey TD, Maehara A, Xu K, Ben-Yehu-da O, Kirtane AJ, Stone GW. Sex differences in the clinical impact of high platelet reactivity after percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stents: results from the ADAPT-DES Study (As-sessment of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy With Drug-Eluting Stents). Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2017;10:e003577.

15. Kang SH, Suh JW, Yoon CH. Sex differences in management and mortality of patients with ST-elevation myocardialinfarction (from the Korean Acute Myocardial InfarctionNational Registry). Am J Cardiol 2012; 109:787-93.

16. Pepine CJ. Ischemic heart disease in women. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47(3 Suppl.):1S–3S.

17. Vaccarino V, Rathore SS, Wenger NK, Frederick PD, Abramson JL, Barron HV. Sex and racial differences in the management of acute myocardial infarction, 1994 through 2002. N Engl J Med 2005;353(7):671–82.

18. Guillaume Leurent, Ronan Garlantézec, Vincent Auffret, Jean Philippe Hacot, Isabelle Coudert, Emmanuelle Filippi, Antoine Ria-lan, Benoît Moquet, Gilles Rouault, Martine Gilard, Philippe Cas-tellant, Philippe Druelles, Bertrand Boulanger, Josiane Treuil, Ber-trand Avez, Marc Bedossa, Dominique Boulmier, Marielle Le Guel-lec, Hervé Le Breton Gender differences in presentation, manage-ment and inhospital outcome in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: Data from 5000 patients included in the ORBI prospective French regional registry. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2014; 107 (5): 291-298.

19. Kuhn L. Gender difference in treatment and mortality of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction admitted to Victo-rian public hospitals: A retrospective database study. Aust Crit Care 2015; 28(4):196-202.

20. Kytö V, Sipilä J, Rautava P. Association of age and gender with ante-rior location of STEMI. Int J Cardiol 2014;176:1161-1162.

21. Masci PG, Ganame J, Francone M, Desmet W, Lorenzoni V, Iacucci I,Barison A, Carbone I, Lombardi M, Agati L, Janssens S, Bogaert J.Relationship between location and size of myocardial infarction and their reciprocal infl uences on post-infarction left ventricular remod-elling.Eur Heart J 2011;32:1640-1648.

22. Jordaens L, Tavernier R. MIRRACLE Investigators Determinants of sudden death after discharge from hospital for myocardial infarction in the thrombolytic era. Eur Heart J 2001; 22:1214–1225.

23. Kosmidou I, Redfors B, McAndrew T, Embacher M, Mehran R, Dizon JM, Ben-Yehuda O, Mintz GS, Stone GW. Worsening atrioventricu-lar conduction after hospital discharge in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention: the HORIZONS-AMI trial. Coron Artery Dis 2017;28(7):550-556.

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a